DIGIT BY DIGIT Methods

The purpose of this

paper is to present the “pseudo division” algorithm and to show how – at the

price of a slight modification of the divisor (referred as “pseudo divisor”) –

this method can compute different functions as logarithms or arc tangents.

This approach is a generalization by J.E. MEGGITT (1962) of an ancient method invented by Henry BRIGGS (circa 1624) to elaborate his logarithm tables.

Known as “digit-by-digit” methods, this class of algorithms is fast and requires only basic operators: adders and shifters.

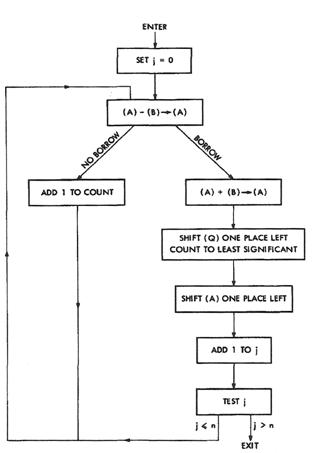

The following chart is extracted from the Meggitt’s paper p.211.

It represents the flow diagram for an elementary divider and it is exactly the core divider implemented in the HP 35’s ROM (the only difference is that register Q is filled in the opposite order in the HP 35 case, from right to left).

The division is

conducted by a rather simple process of repeated subtractions (y/x).

Register A contains the number y and register B the number x. Each register is

correctly dimensioned and the numbers are aligned as needed.

The number of

subtractions is recorded in register Q, which is a counter.

A

small numeric example will make it clear.

A

small numeric example will make it clear.

We calculate 17/5 (y=17, x=5) by repeated subtractions and we note the

calculations as JE Meggitt did p. 214 for logarithms.

The result y/x = 3.4

is just the “decimal expansion” of the quotients digits:

![]()

![]()

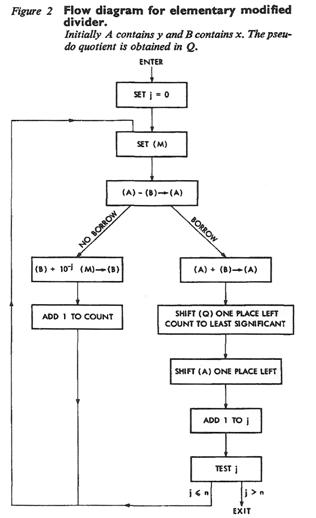

In the second chart

(same page 211), is represented a the flow diagram of a “modified” divider.

After each subtraction the “pseudo” divider, register B on the diagram, is

updated.

The content of the modifier register M, shifted j places to the right, is added

to the divisor:

(B) + 10-j (M) -> (B).

The quotient formed

in the Q register – the

![]() digits-

is named “pseudo” quotient.

digits-

is named “pseudo” quotient.

Changing the modifier can lead to various routines like, log, arc tan, etc.

1) Computing logarithms with pseudo operations.

In the case of the

pseudo divider represented below, the digits

![]() (we

already met in the logarithm article) have been calculated to make the following

expression as small as possible:

(we

already met in the logarithm article) have been calculated to make the following

expression as small as possible:

![]()

This operation

(pseudo division) only differs from a genuine division in that the pseudo

divisor is constantly updated by addition of

![]() (instead

of being constant) (eq 5 Meggitt p. 213).

(instead

of being constant) (eq 5 Meggitt p. 213).

To each pseudo-divider is associated a pseudo-multiplier.

In this case the pseudo-multiplier will calculate

![]() .

.

These digit-by-digit

methods are quite general and it must be understood that the Cordic can be seen

as a particular case were the Briggs’s method is applied to complex logarithm

(e.g. in arc tan calculation, the pseudo quotients

![]() are

calculated to make the imaginary part of the expression

are

calculated to make the imaginary part of the expression

![]() as

small as possible but positive).

as

small as possible but positive).

Let’s elaborate a little bit.

Page 214 of his article, J.E. Meggitt took the example of the pseudo division of y=67719 and x=21608.

Normal division gives: y/x = 3.13397816, but “pseudo division” gives log(1+(y/x)).

The calculation

scheme is -as explained above- slightly different, the “pseudo” divider, x in

register B, is updated, after each subtraction; that gives (to write shorter I

use

![]() in

the expression

in

the expression![]() ):

):

|

j |

B |

A |

Count |

Q |

x' |

y' |

M |

x M |

(x + y) / x M |

|

|

|||||||||

|

0 |

21608 |

67719 |

21608 |

67719 |

|||||

|

|

21608 |

-21608 |

|||||||

|

|

43216 |

46111 |

1 |

43216 |

46111 |

2 |

|||

|

|

43216 |

-43216 |

|||||||

|

|

86432 |

2895 |

2 |

2 |

86432 |

2895 |

4 |

86432 |

1.03349453905961 |

|

|

KO |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

1 |

86432 |

2895 |

0 |

20 |

|||||

|

|

KO |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

2 |

86432 |

2895 |

|||||||

|

|

864.32 |

-864.32 |

|||||||

|

|

87296.32 |

2030.68 |

1 |

87296.32 |

2030.68 |

4.04 |

87296.32 |

1.02326191986100 |

|

|

|

872.9632 |

-872.9632 |

|||||||

|

|

88169.2832 |

1157.7168 |

2 |

88169.2832 |

1157.7168 |

4.0804 |

88169.2832 |

1.01313061372376 |

|

|

|

881.692832 |

-881.692832 |

|||||||

|

|

89050.976 |

276.023968 |

3 |

203 |

89050.97603 |

276.023968 |

4.121204 |

89050.97603 |

1.00309961754828 |

|

|

KO |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

3 |

89050.976 |

276.023968 |

|||||||

|

|

89.050976 |

-89.050976 |

|||||||

| 89140.027 | 186.972992 | 1 | 89140.02701 | 186.972992 | 4.125325204 | 89140.02701 | 1.00209752002825 | ||

| 89.140027 | -89.140027 | ||||||||

| 89229.167 | 97.832965 | 2 | 89140.02701 | 97.83296496 | 4.1294505292040 | 89229.16704 | 1.00109642360464 | ||

| 89.229167 | -89.229167 | ||||||||

| 89318.3962 | 8.603797925 | 3 | 2033 | 89229.16704 | 8.603797925 | 4.1335799797332 | 89318.3962 | 1.00009632727737 | |

| KO |

At the end of each of the 3 possible pseudo-divisions (j=0, 2, 3), the values of

![]() are:

are:

2895, 276.023968, and 8.603797925.

Note that minimizing y’ (small as possible but y’ > 0) is equivalent to drive

the ratio

![]() close

to 1; we will see below that this latter is the most interesting to consider for accuracy.

close

to 1; we will see below that this latter is the most interesting to consider for accuracy.

After the pseudo divisions: y’ = 8.60379792 and the pseudo quotients are “2033”,

so we can form the expression:

![]()

which is already a very good approximation of ln(1 + y/x) = ln (1 + 3.1339781562) = ln(4.1339781562).

In the previous calculation, by making

![]() as

small as possible

as

small as possible

![]() we

have co transformed x and y, and we have - to the limit- y’ = 0, and therefore

we

have co transformed x and y, and we have - to the limit- y’ = 0, and therefore

![]() and

and

![]() .

.

Now, we have to take into account the small difference:

![]()

that is to say :

![]()

![]()

and the result we search is:

![]()

working on

![]() with

with

![]()

it comes:

![]()

In our example:

![]() and

and

![]()

Here we met again the Briggs’

proportionality golden rule (![]() when

t very small ; in modern language

when

t very small ; in modern language

![]() ):

):

![]()

So we add 0.00009632727737 to our previous result , and we have the final result:

ln (1 + 3.1339781562) = 1. 4192403759

It is word for word the definition of the

Brigg’s radix method as a reversible procedure that leads (using the definition

of logarithms

![]() and

and

![]() )

to a number close to 1 where the golden rule can be applied ; the return process

yields the final result.

)

to a number close to 1 where the golden rule can be applied ; the return process

yields the final result.

The only difference is that here the result is found

resolving the number into factors of the form

![]() and

adding the logarithms of the factors.

and

adding the logarithms of the factors.

The Meggitt’s approach is quite general and can be applied to evaluate log z

(instead of log(1 + y/x) by simply taking y = 1 –z, but the original

presentation shows the proximity with the straight division algorithm and the

Briggs’ approach.

I will now show how to derive the former expression from the pseudo-expression recurrence expressions.

We write simply the pseudo division scheme:

![]()

(in the normal division x is constant).

If we bring up (2) in (1), we have:

![]()

![]() (for

a j).

(for

a j).

For k factors, we have (all the recurrences for a j) :

![]()

In practice however, we will make a fixed number of pseudo-divisions (5 in the HP calculators implementation) and expression (3) is never null so we have to take care of the remainder. See the refinements of the actual implementation in the HP 35 ROM.

2) Computing “arc tan x” with pseudo

operations.

The same scheme is applied by J.E.

MEGGITT to the case of the inverse trigonometric functions and it seems

difficult to understand –for many of my readers- that it is exactly the same

algorithm, named CORDIC by J. VOLDER.

The common denominator of these algorithms could be named “digit-by-digit”

methods and they date back to Briggs, 3 centuries ago and were studied by many

authors (e.g. the divide algorithm of the IBM/360 Model 91 that cotransforms

y/x, until the divisor is close to 1 (3) ).

One difficulty is that Meggitt’s does not follow the trigonometric classical presentation for the successive rotation formulas, but uses the complex numbers notation.

This extension to the complex domain is just another paradigm.

I will use very elementary mathematics.

The linear transformation that carries a vector x into another u obtained by

rotating through an angle

![]() is

called a rotation.

is

called a rotation.

We can choose another paradigm and

consider a rotation as the multiplication of 2 complex numbers. As a matter of

fact the complex number z has 2 forms of representation

![]() and

and

![]() (rectangular

and polar) and the product of 2 complex numbers z1 and z2:

(rectangular

and polar) and the product of 2 complex numbers z1 and z2:

![]()

For the inverse trigonometric function,

the process starts from a point in the plane

![]() representing

the complex number :

representing

the complex number :

![]() or,

or,

![]()

by definition

![]() and

and

![]()

Now we rotate the vector “clock wise” to

the x axis, minimizing thus the Y component and counting the number of rotations

(![]() )

for each small angle

)

for each small angle

![]() .

.

We start the series of rotations by the angle

![]() .

.

This rotation clock wise writes:

![]() (the

negative sign expressing the clock wise rotation and the angle is

(the

negative sign expressing the clock wise rotation and the angle is

![]() .

.

Now we can see how the Cordic rotations transform in digit-by-digit recurrence

expression (as written by Meggitt).

We write the first rotation:

![]()

then we expand :

![]()

Finally we have the recurrence formulas:

These formulas are very close to the logarithm recurrences established above, but the pseudo divisor is different:

![]()

3) Briggs, Meggitt, Volder, and others.

The Cordic algorithm (Volder 1956) is

nothing but a trigonometric application of the “digit-by-digit” methods known by

Briggs and others three centuries ago.

Meggitt applied (1962) the pseudo division and pseudo multiplication methods to

a number of functions.

A lot of authors are re-discovering –from time to time- this approach, bringing

enhancements (speed and/or accuracy).

There is nothing magical in this

parentage: the basic root scheme is an iterative cotransformation of a pair of

numbers (x,y) leaving a bivariate function F(x,y) invariant (cf. 7).

You’ll find below ancient tracks to follow.

Jacques Laporte

Friday, 09 June 2006

(1) J.E. MEGGIT, Pseudo Division and Pseudo Multiplication processes, IBM

Journal, Res & Dev, April 1962, 210-226.

(2) J .E. VOLDER, “The Cordic Trigonometric Computing Technique”, IEEE

Transactions on Electronic Computers, Sept. 1959.

(3) S. F. ANDERSON, J. G. Earle. R. E. Goldschmidt, and D. M. Powers,

"The IBM System/360 Model 91: Floating-point Execution Unit," IBM J . Res.

Develop. 11, 34-53 (1967).

(4) Vladimir BAYKOV - Vladimir SMOLOV: "Hardware implementation of the

elementary functions in computers" (in Russian), 1975, Leningrad State

University, a few pages published here:

http://baykov.de/cordic1972.htm ,

(5) H. E. SALZER, "Radix Tables for Finding the Logarithm of Any Number

of 25 Decimal Places," in Tables of Functions and of Zeros Functions, National

Bureau of Standards Applied Mathematics Series n° 37, 1957.

(6) J. S. WALTHER, "A Unified Algorithm for Elementary Functions," Proc.

AFIPS 1971 Spring Joint Computer Conference, pp. 379-385.

(7) TIEN CHI CHEN, Automatic Computation of Exponentials, Logarithms,

Ratios and Square Roots, IBM J. RES. DEVELOP. July 1972.

Note on the “radix method”.

The “radix method” is defined by Florian Cajori (A History of Mathematics, 1893,

p 155) as “A famous method of computing logarithms is the so-called "radix

method". It requires the aid of a table of radices or numbers of the form

![]() with

their logarithms.

with

their logarithms.

The logarithm of a number is found resolving the number into factors of the form

![]() and

adding the logarithms of the factors.

and

adding the logarithms of the factors.

The earliest appearance of this method is in an anonymous "Appendix" (very probably due to Oughtred) to Edward Wrights’s 1618 edition of Napier’s Descriptio.

It is fully developed by Briggs in his 1624 Arithmetica logarithmica (Ch. 14 or Ch. 12 of the Vlacq's edition - available on Google Books).

The procedure followed by Meggitt is in fact the Briggs' method.

There is no hole between Briggs (1624) and Meggitt (1962), and for example,

Robert Flower gives in 1771 (“The radix a new way of making Logarithms”, London)

a description very similar.

Jacques LAPORTE

13/11/2006, revisited Feb 2012

|

|

fig 1 : “Arithmetica Logarithmica” Chapter 14 Radix table

fig2 : same chapter, example of calculation using a Radix table